Farmkeepers Blog

The Farmkeepers is the official blog of NC Farm Families. It is here that words will flow, our voice will be heard, a stand will be made, and the farm families of North Carolina will be protected. In these posts, we'll set the record straight. You'll see the faces of the families who feed us. Here, you'll receive all the updates and news. It is here that we will fight for farmers and be the keepers of the farm in NC. We hope you'll join us. Follow along on social media and by joining our email list.

"Farming is Who I Am": The Smith Family's Story

“Farming is kind of who I am. It’s about heritage. Dad has always done it. It’s what I’ve always wanted to do.”

—Jeb Smith

So often, farming is more than a profession. It becomes an identity, a way of life. It is a flame passed on through the generations. It isn’t always this way, but often it is. For Jeb and Steve Smith, it is.

In 1994 Steve Smith began building hog barns in Albertson. In January of 1995, he sold his first pigs. Like many in eastern North Carolina, pigs were a chance to get out of the tobacco business. By 2000, Steve had completely gotten out of tobacco and put all his efforts into caring for and managing his pig farms.

Steve’s father would come to the farm most mornings until he couldn’t at the age of 90. For Steve, his dad provided a lot of support.

“He was a lot of support and a lot of help,” Steve said with emotion. “Really, he helped me get in the pig business.”

The support and lessons Steve received from his father, were passed down to Steve’s son, Jeb who grew up on the farm helping his dad.

“Jeb’s built a good work ethic. He grew up knowing how to work,” Steve said.

While Steve raised his son on the farm, he never expected Jeb to make farming his life. It was never something he pressured him to do. For Steve, if Jeb is happy with what he’s doing, that’s all Steve wants.

But for Jeb, farming is all he’s wanted to do. He loves being close to home and enjoys working with his dad.

“We work well together. We have our moments like everybody, but not a whole lot,” Jeb shared. “If something does come up, in 30 minutes, we’ve forgotten about it. We’ve moved on.”

Steve said that he and his dad also worked well together—yet another trait being carried on to the next generation.

In addition to working on the farm, Jeb also works with the county’s Soil and Water as a Soil Conservationist. He checks pigs at 5:30 or 6 every morning before heading to work. For Jeb, working with Soil and Water has reinforced his desire to be a good steward of the land.

“Be good to the earth, and it will be good back to you. I’ve always tried to live that way, even before I went to work there,” Jeb said.

Caring for the land is important to the Smith family. Some of their land has been in their family since the 1750’s. Not only do they live on the land that they farm, but they are keenly aware of how the farm is woven into the community.

“It’s nice to have hogs and farm in the same community where we live. We’re the closest hog farm to where we go to church. We can hear the church bells at 12 o’clock at the farm every day,” Steve said.

Additionally, Jeb serves on the local fire department. His wife, Jaiden, is a social worker in Duplin County. Community for the Smiths is something they care about.

When the lawsuits came to their community, it was a hard time. The lawyers came to town, and tensions and divisiveness arose in a normally peaceful, friendly community. Perhaps the best description for the situation was heart-breaking. Friends the Smiths grew up with were sitting in court rooms, facing the loss of their farms.

“It was hard hearing about it as a hog farmer, but it was just as tough listening to it as a person and friend hearing about what they went through,” Jeb said.

Hitting so close to home (one sued farm was 15 minutes away), seeing the toll on farmers and the community first-hand, and even experiencing being sued themselves (the farm was dropped from the suit), the Smiths feel fortunate.

Like many farms, they’ve never received a complaint. Their goal is to not inconvenience others, but with more people moving to the country and farmland disappearing, as Steve said, “we’re running out of room. We’re running out of everything except hungry people to feed.”

Since the farm was built almost 30 years ago, there have been changes, many for the better. While change can be hard for Steve, he says that “we’ve got to accept change.”

Some things, though, don’t change. Community remains important and farming is still what the Smith men want to do, and to do it well.

“It gives you a sense of satisfaction. You try to do a good job,” Steve stated.

And for this farming life that the Smiths have chosen to carry on, they continue to be supported by their family, friends, and the generations that came before.

Jeb and Jaiden got married in 2020.

Steve and wife Kim. Steve said: Kim has always been supportive of what I do. When you have someone who does that, who supports you. It’s really nice.

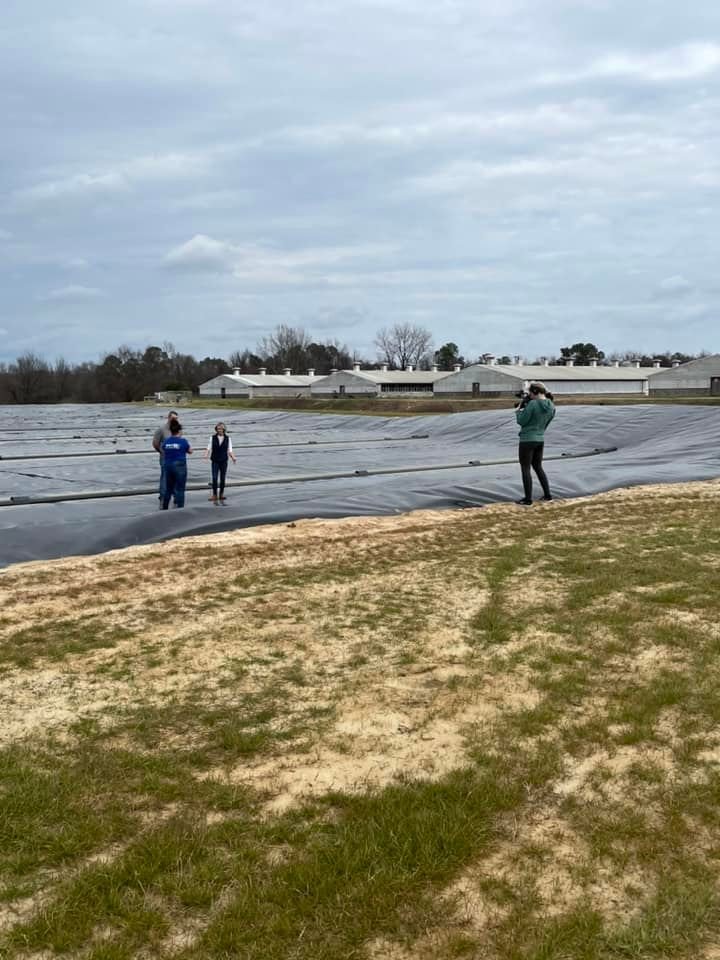

Answering Your Questions About Renewable Natural Gas (RNG) on Hog Farms

Change can be scary. At the vary least, it can raise a lot of questions. With the opportunity to implement renewable natural gas projects on some of North Carolina’s hog farms, there have been many questions raised—questions of safety, impact, and simple curiosity.

While most are excited about the opportunity for NC to become a leader in RNG, there are those that have reservations. And so, we wanted to provide answers to some frequently asked questions. Whether you are a skeptic, a sucker for new technology, a community member, a farmer, or a consumer, we hope this answers some of your queries.

FAQ’s

-

No. Ammonia levels are dependent on the number of pigs. The size of farms, nor the amount of nitrogen on the farm is changing.

-

No it doesn't. Farmers will still be fertilizing crops with wastewater. However, GHG and other farm emissions will be reduced and treatment and storage capacity will be enhanced. The lagoon/sprayfield system is still highly regulated, designed by university professors, and is non-discharge. Learn more about lagoons and spray fields here.

-

Covering lagoons will decrease odor as the emissions from the breakdown of manure will be removed from the farm.

-

Farmers have long been the adopters of innovation. RNG is the next innovative frontier. RNG allows farmers to add another source of income that mitigates manure management costs, while being better stewards of the environment.

-

No. Biogas is the only thing that will leave the farms.

-

The biogas that will be transported through the gathering lines is 30-40% CO2, which is what is in a fire extinguisher. In addition, the pressure in the gathering lines will be very low, less than what is in a car tire. In these conditions, the gas is not explosive.

-

No. The only thing being added is digesters.

-

No new hog farms have been allowed to be built in NC since 1997. RNG does not change this. A modification to current Swine Permits are required to build RNG on existing farms.

-

No. DEQ found that the Swine Permit "did not discriminate on the basis of race, color, or national origin on its face, in its implementation, by its impact, or in any other way." In addition, digesters and RNG are good for the environment as described, so any impacts would be positive.

-

Simply, they have. You can see a map of these farms here. In addition, farmer’s participation is voluntary. As farmers chose to participate, they will apply for permits, and their choice to participate will be known.

-

We think there are different reasons for opposing this innovative technology. 1) people may have misconceptions about RNG. We're trying to provide answers and information to put those misconceptions to rest. 2) Sometimes people just want to be critical and would love it if pig farmers didn't exist.

-

Yes! A recent survey showed that residents strongly support RNG programs

West Family Farm: Deep Community Roots

Lee West is the fourth generation to work on his family’s farm. Although, there’s been difficult times, the farm has grown. Through the years, they’ve never lost sight of their deep family and community roots.

Lee’s great-grandfather had a stroke when Lee’s grandfather, Jerry, was only 13. Most of the farm equipment was sold and the farm was rented out. When his grandfather became an adult, he worked in a local manufacturing plant while farming part time. When his manufacturing job told him he’d need to move out West, it was time for a change. Fremont was home, and that’s where he wanted to stay. So, in 1979, he started farming full-time. There were very few acres at the time and only 1-2 tractors. Today, the farm has grown to 6,000 acres where they grow many crops (read part 1 of the West’s story to learn what they grow).

While they’ve grown, their community and heritage are just as important as it was in the 60’s. Their growth wouldn’t be possible without the community.

Of the 6,000 acres they tend, the Wests rent 5,500 of those acres from landowners. Because the county is cut up so badly, they rent from more than 120 landowners. The agreement benefits both parties by providing income for landowners and land for the West’s crops. The Wests are focused on meeting the expectations of landowners. “Each one has their own concerns and how they want things treated,” says Lee. He adds that “you have to agree with your community and share the road.”

Northern Wayne County has been growing for the last 20 years. Lee says that his dad, Craig, talks about how used to you could drive a tractor 3-4 miles down the road before having to pull over for cars. Now they can hardly get out of their driveway. The Wests understand the importance of mutual respect and try hard to do their part in the community.

“Being a good neighbor and being a good person in the community, you hope that your community will work with you and allow you to get to your fields and grow your hogs,” Lee said.

For some, 6,000 acres may sound huge, and hardly a family farm, but Lee says that they are definitely a family farm. He, his dad, his uncle, and other family members are hands-on every day. When asked what it meant to be a family farm, Lee said, “It’s the pride. We all know what’s going on. We can tell you everyone’s name, their kids, and where they’re from. As progression progresses, we have had to tend more acres, buy more equipment, hire more workers, but I still like that smaller family farm mentality we have. We may not be as efficient as other farms, but we take pride in it and do the best we can.”

Lee also wishes that people understood that farming isn’t just about driving tractors. It’s a lot of business. The Wests have a farm office where Lee’s aunt, Lynn, and grandmother, Audrey, handles office reports, payrolls, taxes, and a host of other paperwork. That business is a big part of the local economy, benefiting many local businesses in the community.

For the Wests, business, farming, and the community are combined by taking the time to sit on various boards. In addition to local county groups, Craig is a board member of NC Sweetpotatoes and the Tobacco Growers Association while Brad sits on the board at NC Peanut Growers. Sitting on these boards allows these gentlemen to give not just a farmer’s perspective, but a resident of rural Wayne County. They are voices for and in their community.

Apart from being a good neighbor or business partner with those in the community, the Wests are also passionate about building relationships with their community. Many of those relationships are built over strawberries. In 2013, Lee’s aunt and uncle started a strawberry patch, and in 2019, Lee and his wife, Madison, took it over.

“My favorite part about strawberries is Saturdays. I get to see everybody from all over Wayne County. They bring their kids for the U-pick. Our customers come back week after week and year after year, and I think that’s the coolest part,” Madison said.

The effort is one of the heart, not necessarily for business.

“The strawberries are for the community more or less now,” Lee says. “The strawberries can be tough. They take a lot of time.”

Yet, you can find Madison in the strawberry barn on Saturdays during strawberry season, excited to see those in the community.

“They’ve become family to us too. Community is the biggest part of farming, to me,” Madison shares.

Lee & Madison at the Fremont Christmas Parade